I grew up listening to the stories that my grandfather, Salvador, told us about his childhood in Barcelona: what it was like to move there from Argentina when he was about ten years old, his teenage escapades, and, eventually, being drafted to fight for the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War. He spared us the gory details, probably to preserve his sanity and to protect our childhood innocence.

To me, Barcelona felt very distant and familiar at the same time. In my imagination, it was a mythical land stuck in the time when all my granddad’s stories took place. He was born in Buenos Aires, but his parents, who were Spanish, decided to return to the Motherland. Salvador and his family arrived in 1928 and lived there until after the Spanish Civil War. He chose not to return to Spain, not even for a visit, so he never knew the thriving, modern Barcelona I visited and fell in love with.

Santa María del Mar, the book

A few years ago, browsing titles at a bookshop, I came across a novel called La catedral del mar, The Cathedral of the Sea. Published in 2006, it was written by Spanish lawyer and author Ildefonso Falcones. The blurb piqued my interest: a tale of faith, love, betrayal, and resilience set in 14th-century Barcelona, with the Inquisition thrown in. I cannot resist a historical novel, especially one set in this city, so I bought it.

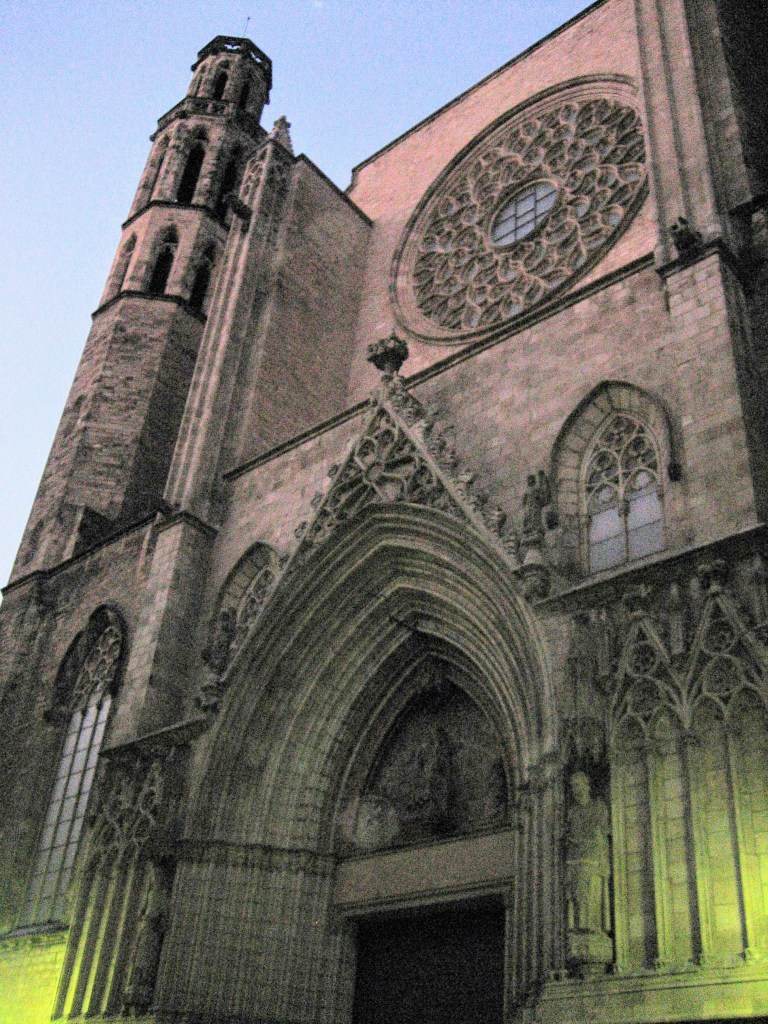

The Cathedral of the Sea braids the story of Arnau Estanyol, a laborer’s son and bastaix (more on that in a moment), with that of the Cathedral of Santa María del Mar, built by the people for the people in Barcelona’s Ribera district in the 14th century, between 1329 and 1383. While Arnau is a fictional character, the church is very much real and influenced my decision to come to Barcelona.

Santa María del Mar is the result of the religious fervor and economic prosperity of its time. The Ribera locals wanted to express their faith by replacing the existing church with a much grander building dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Local merchants and guilds contributed in some way, be it money or hard labor.

The bastaixos

Enter the bastaixos. At the time, Barcelona lacked a port, so ships had to come as close to the shoreline as possible. Then, the bastaixos, or porters, unloaded the cargo and carried it on their backs to the warehouses. They were devoted to the Virgin Mary, but also poor, so the only contribution they could make towards the building of the church was their labor. So they carried the stones one by one from the Foixarda quarry up the Montjuïc.

The bastaixos’s titanic effort was immortalized in copper figures on the main door of the church. Incidentally, according to family lore, a distant cousin of my grandfather’s was accused of treason and executed on Montjuïc during the Spanish Civil War

Arnau Estanyol, the protagonist of La catedral del mar, became a bastaix as a young boy. The building of the cathedral also serves as a backdrop to Arnau’s life and a symbol of the faith and resilience of Catalonians.

The descriptions are so vivid that I felt I was there with Arnau and the bastaixos, carrying stones with them and celebrating every milestone in the building process until the cathedral was finished. Arnau’s excitement about the building is infectious. If I were a religious person, I would say that so is his faith.

The novel was such a fascinating read that I gave it to my mother, who is also an avid reader. She enjoyed it so much that she passed it on to her father, Salvador, closing the circle.

Visiting the real Santa María del Mar

New Year’s Eve in Barcelona. The city is overcrowded with tourists. A human tide ebbs and flows along the Ramblas, the lively pedestrian street that connects the Plaça de Catalunya with the Old Port. My husband and I had driven from the peaceful countryside of southern France, and the contrast could not have been greater. The crowds make the city feel claustrophobic.

After a day battling the crowds up and down Mount Tibidabo, we return to Barri Gòtic, the old town. I am on a mission: visit Santa María del Mar. My husband sits for coffee al fresco at the Plaça de Santa María. I go inside the church. A baptism ceremony is underway. I want to be respectful, but I also want to see everything. I quietly walk and take everything in.

As I read the book, I formed a vague image of what the cathedral looked like, a hodgepodge of features I had seen in other medieval churches. It took me a while to reconcile this with the real thing, which did not fit my idea of a medieval building bathed in multicolored light coming in through stained-glass windows.

The interior of the church is remarkably plain, in keeping with the Catalan Gothic style. However, I find its stark beauty captivating. I am excited to be here and feel a strong connection to my roots. The stream of prayers in Catalan feels like a warm embrace. I do not understand much, but the sounds take me back to family get-togethers, where the family’s elders chatted in rapid-fire Catalan. It puts a smile on my face.

I joined my husband at the outdoor café. From the table, I can see the bronze figures of the bastaixos on the main door of the church. I think of the inhuman effort they made carrying the heavy stones down from the quarry and lifting them into place. I silently thank them for this beautiful church that connects the past, the present, and the future.